BY JONATHAN BALL

Half a million dollars could be sitting in your attic.

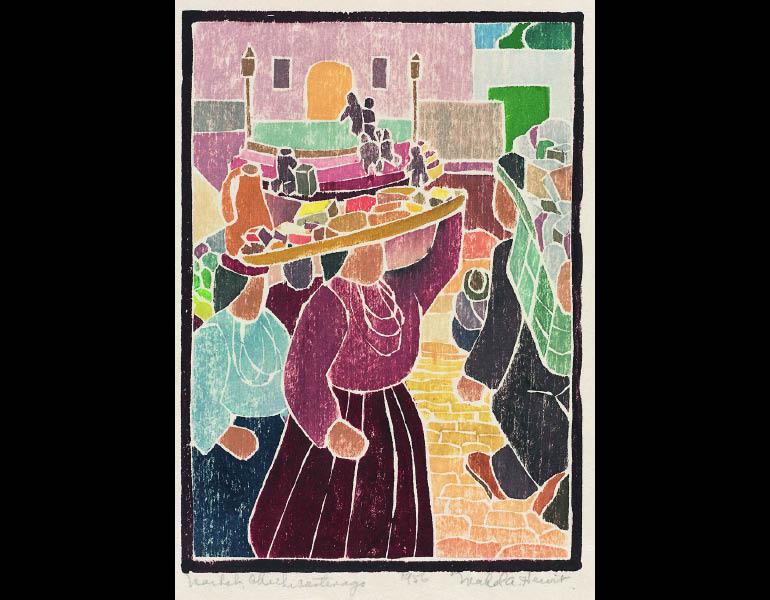

For Jason Jurey, a biology teacher at Wadsworth, those dollars really were waiting for him. Mabel Hewit, Jurey’s aunt, once had an entire exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art. The show was comprised of pieces found in Jurey’s family home.

Jurey’s father was reading the paper one day in 2009, where there happened to be an article on a certain woodblock artist.

“There was an article in the Beacon Journal on this lady who had a display at the Cleveland museum. She was second to none, best in the world.” Jurey said.

Hewit studied under Blanche Lazzell, famous for her white-line woodcuts that feature richly inked wooden prints with outlines that are left uninked. This technique gives the prints a crisp and whimsical feeling reminiscent of classical fairy tale illustrations.

Lazzell was a pioneer in her medium, and Hewit’s connection made her prints extremely valuable.

“My grandparents had boxes of her stuff, since they were cleaning out their attic. He called the museum and the lady he spoke with asked if she could come see the prints that day. She comes and starts leafing through [the prints], and my grandpa says you could see her eyes get bigger and bigger,” Jurey said.

Jurey and his family had a fortune’s worth of art in their attic, but they refused to take payment for it.

“[The curator] told us ‘Your aunt was trained by this woodblock artist, and that alone makes anything she did valuable.’ It was exciting. Once we knew what had happened, and why she was famous, It made me want to learn about her history,” Jurey said.

They donated their collection to the museum in Hewit’s memory.

In the summer of 2010, Hewit’s personal exhibit was unveiled. From June to October, Midwest Modern: The Color Woodcuts of Mabel Hewit took patrons through the works Jurey and his family donated. Some of her most popular pieces remain in the museum to this day, even after her moment in the spotlight is over.

Jurey’s family had no idea how valuable Hewit’s pieces were before the curator informed them.

“My grandparents had this sheet, it was a mural in the Warhol style. My grandparents used to use it to throw over our thanksgiving table. So it now is hanging behind glass at the Cleveland Museum, and it probably still has some cranberry stains on it,” said Jurey.

Hewit was a recluse. She spent most of her time working on her creative passions, and she did more than just woodcarving, according to Jurey.

“The funny thing is that the thing she was recognized for was just a hobby to her. She put her passion into jewelry,” said Jurey.

Artists dedicate themselves to their work, and Hewit was no exception. She poured her heart into the jewelry she wore and she took Lazzell’s teachings to heart.

Sadly, Hewit was not able to see her art recognized in a renowned museum.

“She died when I was too young to even remember, so I really had no interaction with her at all,” he said.

Hewit passed away in Cleveland in 1984, where she spent the greater part of her life toiling away on her art.

“The one memory [my dad] always talks about is that she was always doing something artistic,” Jurey said.

Jurey has a newfound respect for the effort artists put into their craft, and for the rewards they can sometimes receive. He told us how speaking on his aunt’s behalf at the opening for her exhibit was a big change in his perspective.

With a final piece of advice, Jurey says, “Support your local artists. You never can tell who’s going to be the next major breakthrough.”

![Wadsworth's Class Of 2025 Walks At Graduation Ceremony [Photo Gallery]](https://wadsworthbruin.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_9018-1-1200x800.jpg)