BY JULIA BLAKE

Bleak, empty walls. Slamming doors followed by total silence. Chairs bolted to the floor. Children standing idly with their heads down. Stacks of books lining the floors. This is the life of an incarcerated juvenile.

Upon arrival, residents, as opposed to inmates, have just a few short hours to get acquainted to their new life. A ten minute shower, a lice treatment, a two hour reading session and a test is the only welcome they get. A new world awaits them within their four cell walls.

Residents awake at 6 A.M. each day, and the hours of 8 A.M. to 2 P.M. are mandated to schooling. However, their education is limited to two classrooms and a computer lab. Their lunch is served with 20 minutes of complete silence.

There is very little interaction at all between the residents. Only one to two hours of talking is permitted from each resident per day. This lack of socializing leaves residents with long, solitary hours.

“[In their spare time] they do a whole lot of reading”, explained Megan Millikin, assistant superintendent of the juvenile detention center of Medina County.

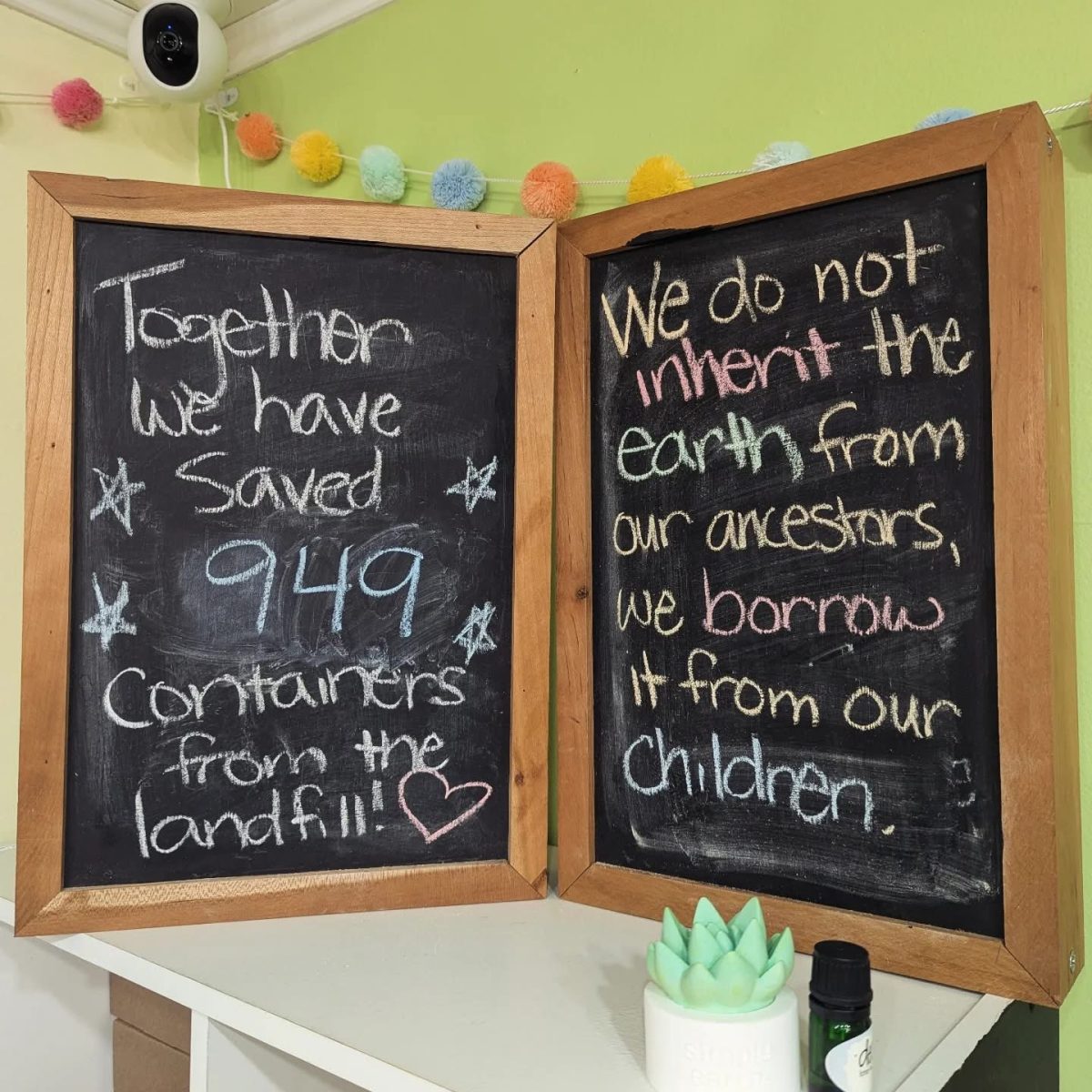

While there are about 1,200 books in the center’s library, residents are only permitted to check out books deemed appropriate for them. With that, many are left with limited options for enrichment and entertainment. To further encourage education, each resident is guaranteed art classes with teacher Carrie Sellars.

Sellars describes art therapy as the one time where residents get to express themselves in whatever way they choose. This creative freedom is the closest thing to normality these children can get in their current situation. In fact, the detention center holds an art show to show families and visitors their creative side.

Apart from the schooling, residents at the center are left with long, solitary hours. This time is mostly spent in their cells with only a bed, a sink, a toilet, and a tiny window for light.

Residents work on an incentive system. If the resident has good behavior consistently, they have the opportunity of receiving an extra phone call per week, accessibility to crayons and markers for recreational purposes, or the possibility to assist in facility cleaning. Upon achieving these privileges, residents have the possibility to have a free bag of potato chips during movie night. Something else they can work to achieve is having one picture of parents, grandparents, or pet in their cell. It is awful to try and picture a life like this, but it is the sad reality of some youth in America.

The juvenile center is aimed toward rehabilitating troubled youth and teaching them the importance of responsibility. Some residents are here for around 21 days while others stay to an upwards of ninety days.

“Unfortunately, most kids that come through once will be back again. We can’t keep them from doing bad things the second they leave the center,” said Millikin.

Shockingly, the center’s youngest resident first entered the system was the age of nine. As for the record number of returns to the center, the center has seen someone return 20 times. If kids do not break the bad habits that got them into the center in the first place, they will inevitably end up back in a center.

According to “The Steep Costs of Keeping Juveniles in Adult Prisons” by The Atlantic, 200,000 youth are incarcerated in the United States each year.

Knowing that there is a world beyond the walls of Wadsworth High School where the halls are filled with silence is a difficult truth to swallow. Most people will never see this side of today’s youth and will never have to. However,for those who have experienced incarceration, this is their life.

This story was printed in February. For more print articles, check out the full issue: